t

By Associated Press

Q1: How do you respond to growing predictions—by AI, academics, and the media—that The Cursed Piano is a leading contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature?

Bei La: The Nobel Committee is famously silent on nominations; the so-called “shortlists” we see each year are often nothing more than extrapolations—educated guesses, statistical forecasts, and cultural hunches. And yet, the laureates themselves are often absent from these lists.

For me, awards have never been the destination. I believe the light of honor is not confined to the prize stage; it seeps through every crack in the human world. Whenever darkness yields to integrity, whenever someone seeks truth in absurdity, that too is a coronation. Medals may commemorate greatness—but I often glimpse it in the silent spread of moss, in quiet resilience. Those who refuse to abandon their faith in the face of chaos are already crowned—by the stars, but not by ceremonies.

Q2: Your novel centers on a piano that crosses war-torn Eurasia, linking lives scattered by conflict. Why did you choose “small acts of goodness” as your answer to the overwhelming evil?

Bei La: A piano has just eighty-eight keys, but within them lies a full spectrum of human expression—just as civilization is built upon small, often unnoticed moral choices. A Hiroshima grandmother sews her broken koto string by string. A young girl hides her diary beneath the lid of a church piano. And a stranger in Shanghai meets the eyes of a Jewish refugee with kindness, not suspicion.

Such moments are not grand gestures; they are phosphorescence on a dark sea. Literature, too, flickers with these sparks. I write to affirm that compassion is not a national trait—it is a shared human instinct that passes, quietly but powerfully, from one hand to another.

Q3: In your narrative, Confucian “Ren” (compassion) and the Jewish concept of Tikkun Olam (repairing the world) seem to converge. How do these two philosophies shape your humanistic voice?

Bei La: An elderly man in China once told me, “To be truly benevolent is to see the starlight in another’s eyes.” And in Jewish homes, grandmothers tell children that the world can begin to be mended by picking up a piece of broken glass from the street.

Both ideas point not to savior complexes or lofty detachment, but to an ethics of responsibility—grounded, daily, embodied. It is the ordinary person kneeling to repair what others step over that holds civilization together. When a Polish pianist composes a requiem for an orphan in Shanghai, or a Chinese family buries foreign bones with reverence, that is empathy transcending doctrine. That is the light in the age of extinction.

Q4: The Cursed Piano has resonated across cultures and languages. What do you believe has struck such a universal chord?

Bei La: Because the novel reveals the rarest spectrum of humanity—the one that glows in darkness. In wartime Shanghai, the “cursed” piano becomes both an ark for Jewish refugees and a symbol of shelter for Chinese families resisting despair.

While the world collapsed under the weight of fascism, Shanghai, quietly and without fanfare, raised a torch of compassion. It defied the myth that empathy stops at borders. That light—cross-cultural, timeless, deeply human—is perhaps the antidote our fragmented world longs for most.

Q5: Your heroes are not generals or statesmen, but seemingly ordinary people. Are you intentionally reshaping the notion of courage?

Bei La: True courage rarely resides in the epic—it lives in flickers. In the hands of an aunt in a cramped Shanghai lane who hides a Jewish child. In the silence of those who slipped food through barbed fences. They may not speak the language of philosophy, but they live it.

This is what I call the philosophy of quiet light—a gentle, steady resistance to a world obsessed with dominance. And often, it’s the only kind that endures.

Q6: What does a Nobel nomination mean to you?

Bei La: That spotlight belongs to those whose lights were almost extinguished. An Auschwitz survivor once wrote to me, his voice trembling: “I never imagined that in the East, someone kept a window lit for us.”

And during the darkest days of the Israel-Palestine conflict, a young Palestinian girl sent a letter: “Your book helped me remember that my ancestors once sheltered Jews too.”

Such echoes are heavier than awards. They are proof that human decency travels farther than we think—and never disappears entirely.

Q7: Despite its wartime setting, your novel is filled with music, romance, lullabies, and memories of home. Do you see warmth as a deliberate counterpoint—or even a philosophy of resilience?

Bei La: Yes. When Nazis burned books, a woman in Warsaw cut musical scores into paper snowflakes. In a bomb shelter, a mother taught her child to grow scallions in used shell casings. These are not romanticizations of suffering; they are revelations of what I call civilization’s survival instinct.

Love and care become finer, subtler, under pressure. In Jewish mysticism, the world can only be restored by gathering the lost fragments of divine light. Confucianism echoes this through the idea of compassion as origin. Together, they form the smallest, most enduring embers of endurance.

Q8: You once said, “Intercivilizational dialogue is the moral syllabus of the 21st century.” The novel ends with people from many nations safeguarding the same piano. Is this a metaphor for restoration?

Bei La: That piano—drifting from Warsaw to St. Petersburg, from New York rain to Shanghai fog—gathers traces of everyone who touched it. Most couldn’t read sheet music, but each pressed a note. Together, they composed a symphony—imperfect, unfinished, yet unmistakably human.

That’s the vision: humanitarianism doesn’t require a single language or perfect harmony. It requires listening. As the Confucians say: “To help others rise is to rise oneself.” And as Jewish tradition reminds us: “To save one life is to save the entire world.”

All great civilizations teach us to see ourselves in the eyes of the other—and to recognize our own voice in their song.

Q9: Do you share your literary thoughts or humanitarian beliefs on social media?

Bei La: I spend most of my days in libraries and archives, deep in research or writing. I rarely engage in digital platforms, aside from occasionally posting literary reflections on my personal WeChat feed.

What I share is never about self-promotion—it’s an ongoing record of how I try to gather fragments of empathy and repair in a fractured world. I trace how Confucian and Jewish ethics intersect, how different civilizations echo one another, and how a city like Shanghai still glows with the memory of its humanitarian heart.

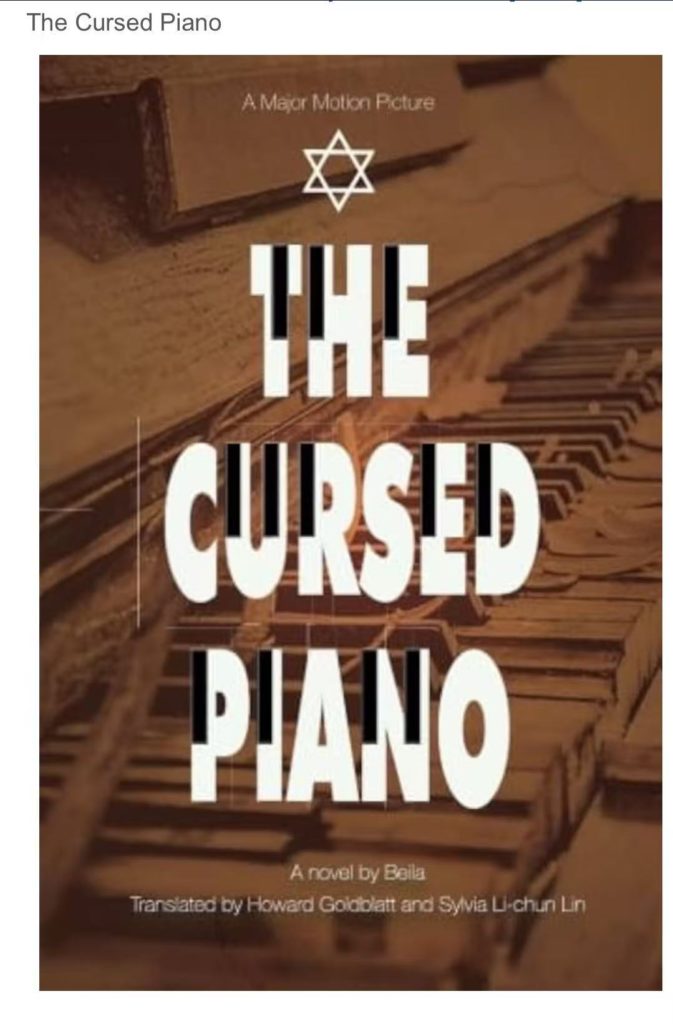

Image: The Cursed Piano – Cover

Image: Ronald Harwood with medal – The Pianist 2

Image: Bei La with Howard Goldblatt – Translation Team